Korea’s Healthcare System Part III: Ensuring Equitable Access to Healthcare for All Households

Korea’s Healthcare System Part III: Ensuring Equitable Access to Healthcare for All Households

Published September 4, 2024

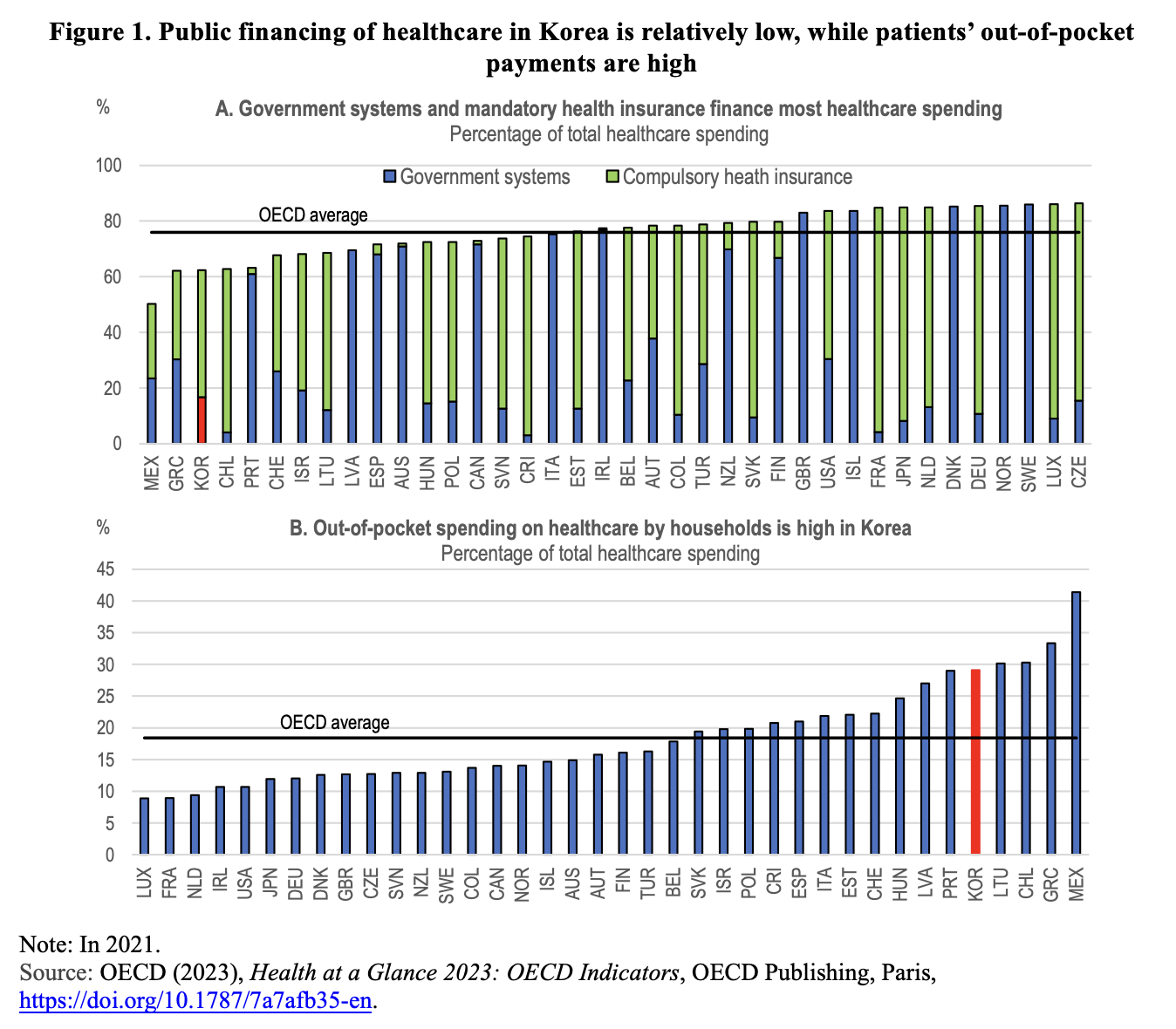

The public sector financed 76 percent of healthcare in OECD countries in 2021 using compulsory health insurance and government programs (Figure 1, Panel A). Korea is an outlier in this regard, as only 62.3 percent of its health expenditures were covered through mandatory financing schemes. The low share of mandatory financing in Korea was offset by a high share of out-of-pocket payments, which financed 29 percent of health expenditures in 2021, the fifth-highest share in the OECD and 11 percentage points above the OECD average (Panel B). The share of out-of-pocket payments in OECD countries tends to decrease as per capita income increases. Households accounted for 30 percent or more of all healthcare spending in Mexico (41 percent), Greece (33 percent), Chile (30 percent), and Lithuania (30 percent), while in France, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg, out-of-pocket spending was below 10 percent.

Reasons for Korea’s Relatively High Out-of-Pocket Payments and Its Impact

Out-of-pocket payments include co-payments for services covered by Korea’s National Health Insurance (NHI) benefits package and complete payments for out-of-coverage services. The standard co-payment rate on insured services for inpatient care is 20 percent and between 30 and 60 percent for outpatient care, depending on the level of provider (i.e., physician clinics, hospitals, general hospitals, and tertiary care hospitals).

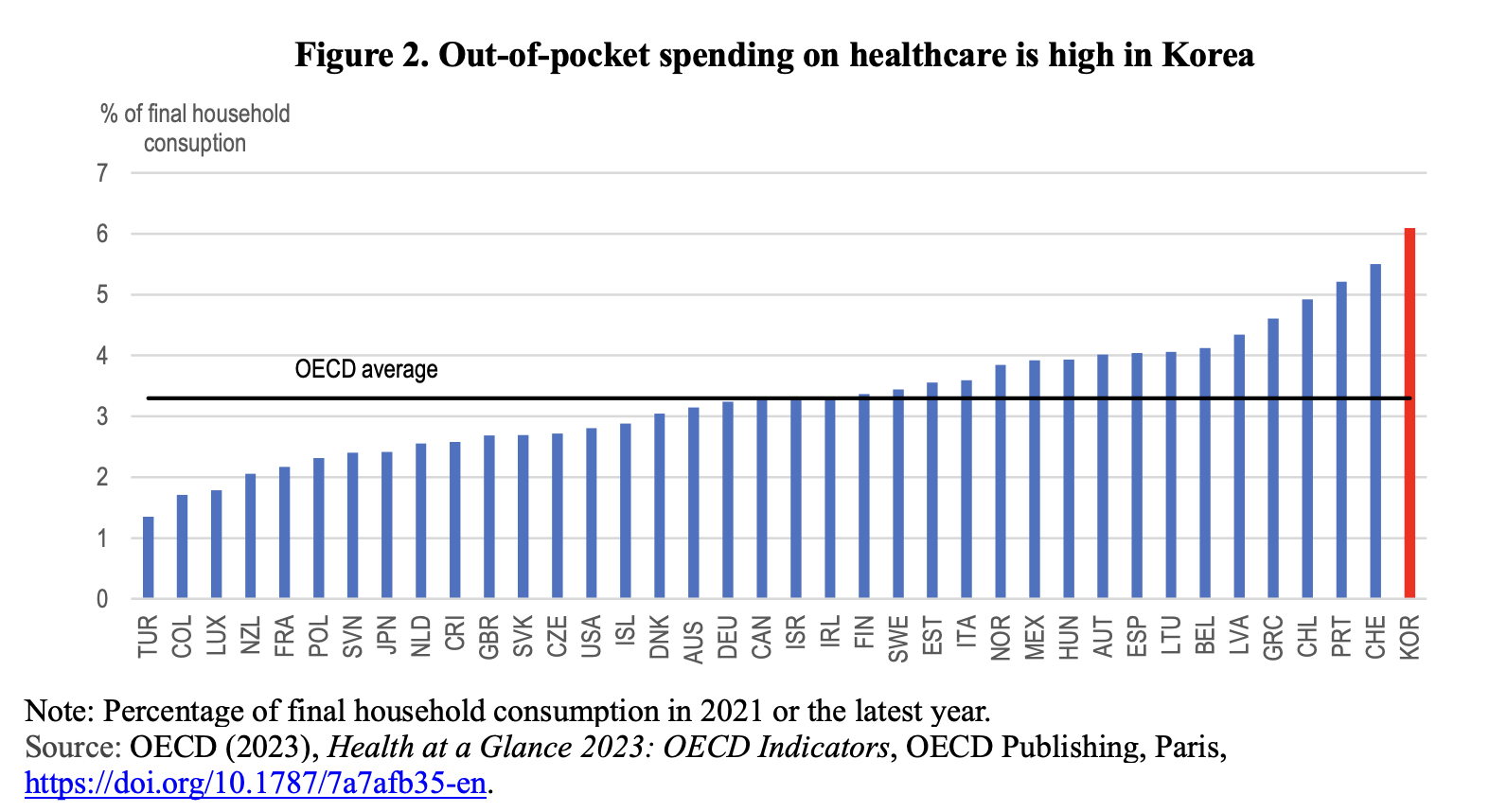

High out-of-pocket payments can lower overall healthcare costs by reducing the use of unnecessary healthcare services and goods. Cost-sharing makes consumers more selective and careful in their healthcare choices, as they are responsible for a larger portion of the cost. The significant role of out-of-pocket payments boosted healthcare spending in Korea to 6.1 percent of final household consumption in 2021, the highest among OECD countries and nearly double the OECD average (Figure 2).

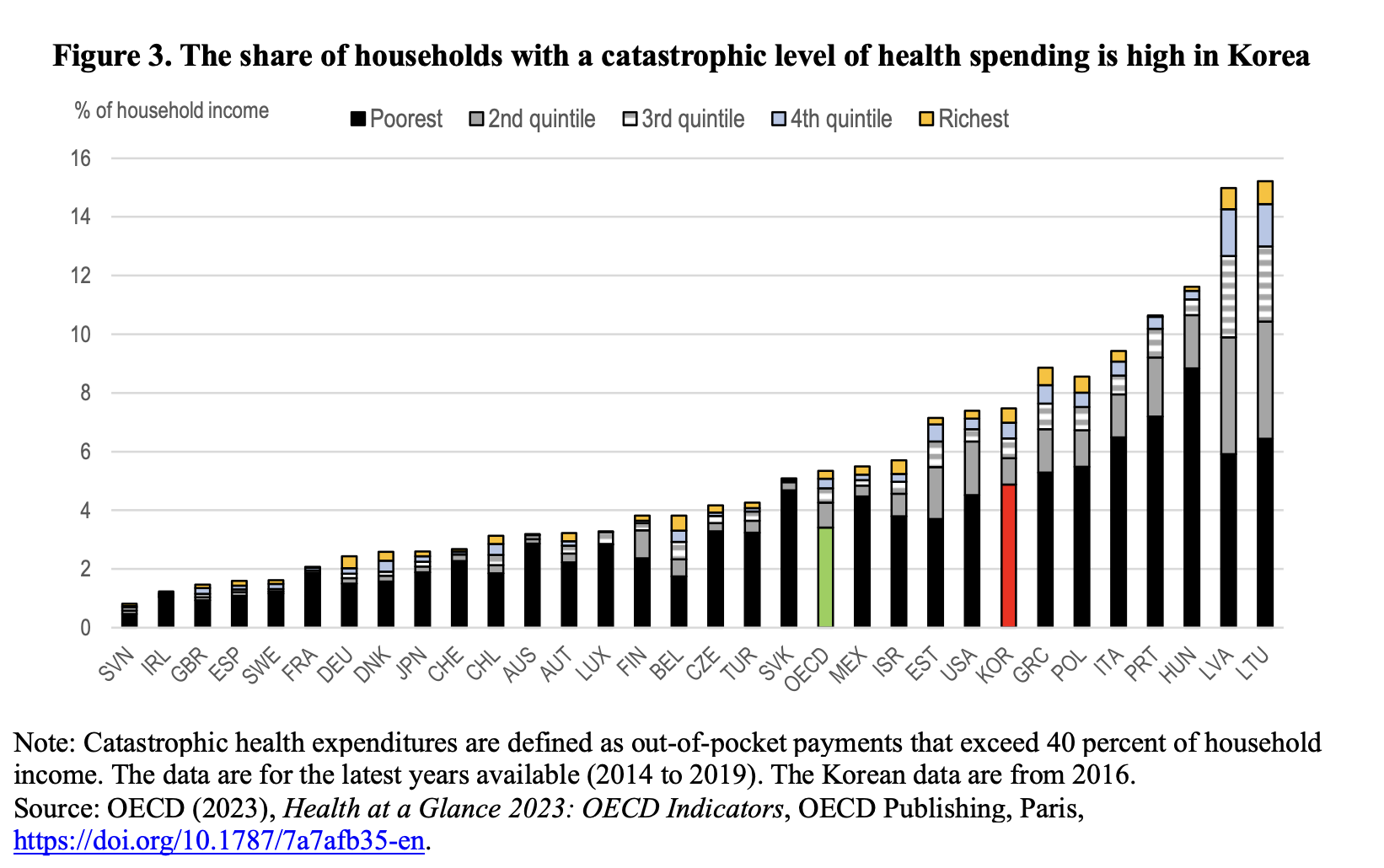

However, the high share of out-of-pocket payments may impose significant burdens on vulnerable persons. Indeed, the share of Korean households facing catastrophic health expenditures, defined as out-of-pocket payments exceeding 40 percent of household income, was 7.5 percent in 2016, more than 2 percentage points above the OECD average (Figure 3). Households in the lowest income quintile accounted for two-thirds of those facing catastrophic health expenditures, while those in the highest quintile accounted for only 7 percent. In particular, the high level of out-of-pocket payments may limit elderly persons’ access to healthcare. One study found that 17.4 percent of the elderly in Korea had unmet healthcare needs, primarily due to economic hardships. Unmet healthcare needs increase illness severity, complications, and mortality.

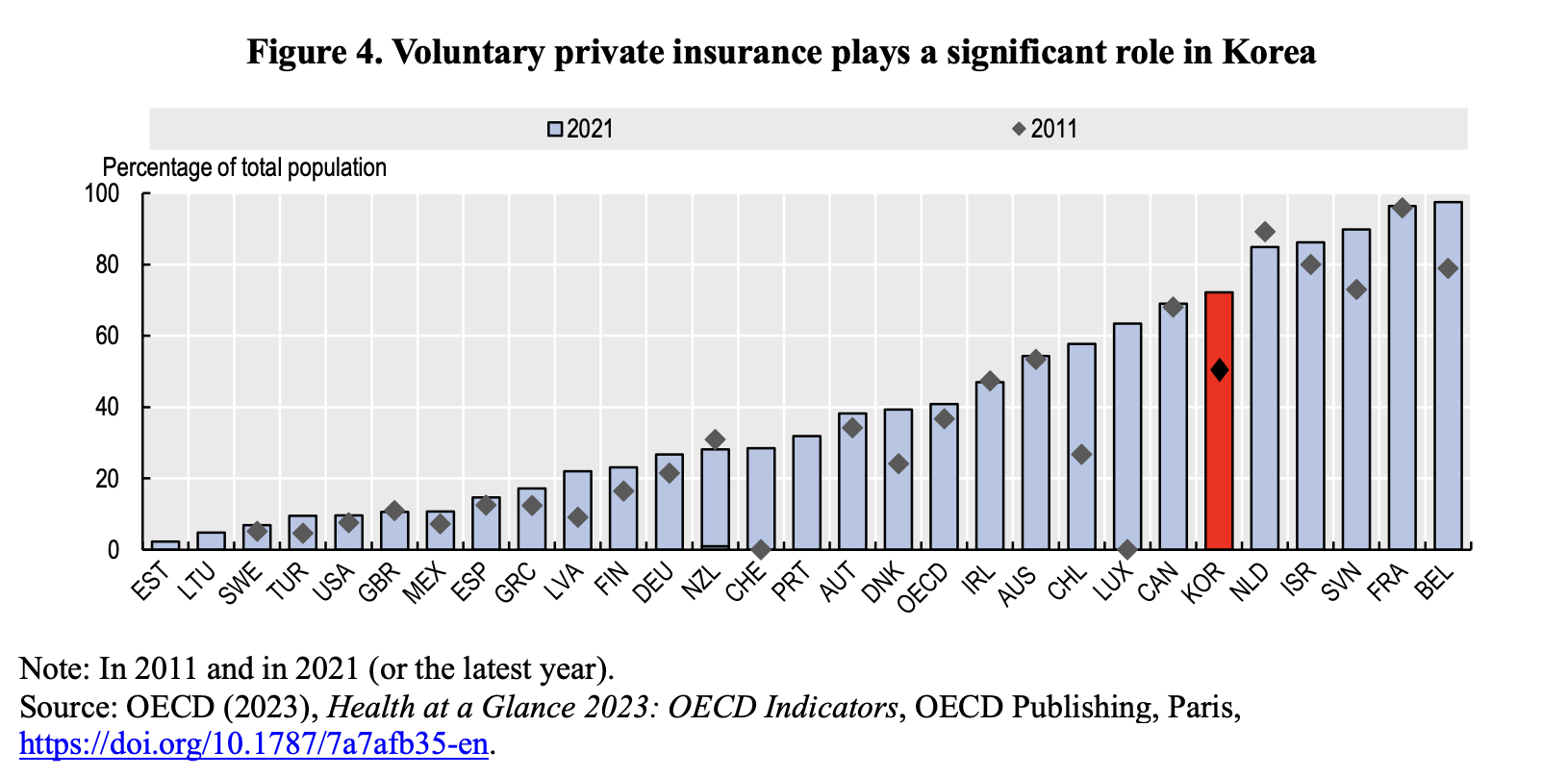

In many countries, including Korea, additional health coverage through voluntary private health insurance is available. Among 28 OECD countries with recent comparable data, over half of the population in 11 countries, including Korea, had private insurance coverage in 2021 (Figure 4). In Korea, private insurance can be complementary (i.e., covering co-payments on services covered by the NHI) and supplementary (i.e., covering services not included in the NHI). The share of the population in Korea with voluntary private health insurance rose from 51 percent in 2011 to 72 percent in 2021, reflecting the large out-of-pocket payments and gaps in the NHI. In 2021, voluntary private health insurance financed 8 percent of Korea’s health expenditures, which was double the OECD average.

Policies to Ensure Adequate Access to Healthcare for All Households

The social and economic costs of unequal access to healthcare among low-income households are significant. A number of empirical studies in various countries suggest that poor access to healthcare is associated with lower productivity of workers and shorter healthy life expectancy. To provide better access, low-income persons in Korea are exempt from cost-sharing at the point of service, and vulnerable groups (e.g., the elderly and patients with catastrophic conditions such as cancer) have access to discounted co-payment rates. There is also a ceiling on out-of-pocket payments during each six-month period, with differential ceilings applied to specific income groups.

The Korean government launched an ambitious plan in 2017 to expand insurance coverage to all health services, except non-essential medical care such as cosmetic surgery, by 2022. The strategy reflects concern over the faster increase in out-of-pocket costs for non-covered services than for covered services. Most uncovered services involve new technology and medicines, which tend to be expensive. NHI coverage has been expanded to include expensive services, such as MRI and ultrasound scans. In addition, co-payment rates for many other healthcare services have been reduced. In 2018, the government introduced a financial assistance program for catastrophic medical expenses, refunding 50 percent of co-payments exceeding 1 million KRW (741 USD) per year for low-income households earning less than half of the median income (around 15 percent of the population). In 2021, the government raised the refund rate to 70-80 percent.

The expanded coverage of the NHI and reduction in some co-payment rates helped reduce out-of-pocket expenses from 33.7 percent of healthcare spending in 2017 to 29.1 percent in 2021 (Figure 1, Panel B). Consequently, the public sector’s share of healthcare spending increased from 58.9 percent to 62.3 percent over the same period, though it remains below the government’s target of 70 percent by 2022. Further raising the public sector’s share requires expanding the range of services covered by the NHI based on careful cost-benefit analysis of new services and products. This should include inpatient and outpatient care, where the public shares of healthcare spending were both 22 percentage points below the OECD average in 2021.

Further consideration could be given to adjusting Korea’s high co-payment rates. For the high-income elderly population, out-of-pocket healthcare costs account for only 20 percent of their income, reflecting their lower co-payment rates (compared to 29.1 percent for the entire population). This suggests inequity in healthcare access. Setting co-payments based on income levels rather than age would improve access to healthcare.

Another priority to improve access to healthcare is to increase the coverage of health benefits under the Basic Livelihood Support Program (BLSP), which, in principle, are available to persons with a disposable income that is 40 percent or less of the national median. However, in 2017, only 3 percent of the population had access to BLSP health benefits, far below the 17.3 percent of the population with an income below the relative poverty threshold that year. The small share is due in part to the “family support rule”—low-income persons cannot receive the BLSP healthcare benefit if they have family members, notably parents or adult children, who could provide support. However, the family support rule does not apply in households where at least one person receives Basic Old-Age Pension. Completely abolishing the family support rule would have increased total payments for BLSP health benefits in 2020 from 7 trillion KRW to 11 trillion KRW (5.2 billion USD).

Conclusion

Limited access to healthcare for segments of the population results in significant economic and social costs. Policies to enhance access and reduce the share of the population facing catastrophic medical bills are thus a priority, along with measures to increase the efficiency of healthcare services and limit spending increases. Further expanding the range of services covered by the NHI, based on careful cost-benefit analysis of new services and products, is key to reducing out-of-pocket payments by patients. In addition, high co-payment rates could be adjusted to promote healthcare access while seeking to prevent an increase in unnecessary healthcare services and goods. Co-payment rates should be determined by the income, rather than the age, of patients.

Randall S. Jones is a Non-Resident Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Shutterstock.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.

link