Mental health and related issues statistics

Deaths from mental and behavioural disorders and intentional self-harm

In 2020, there were 194 000 deaths in the EU resulting from mental and behavioural disorders, equivalent to 3.7 % of all deaths. Relative to the population, there were 39 deaths from mental and behavioural disorders per 100 000 inhabitants in the EU in 2020.

Mental and behavioural disorders were a particularly common cause of death at advanced ages. The EU standardised death rate from mental and behavioural disorders in 2020 for those aged 65 years and over was 44 times as high as the standardised death rate for persons aged less than 65 years. This can be compared with the same ratio for all causes of death, where the death rate for those aged 65 years and over was 22 times as high.

Among mental and behavioural disorders, dementia was the most common causes of death in the EU among those over 65 years

(per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_cd_asdr2)

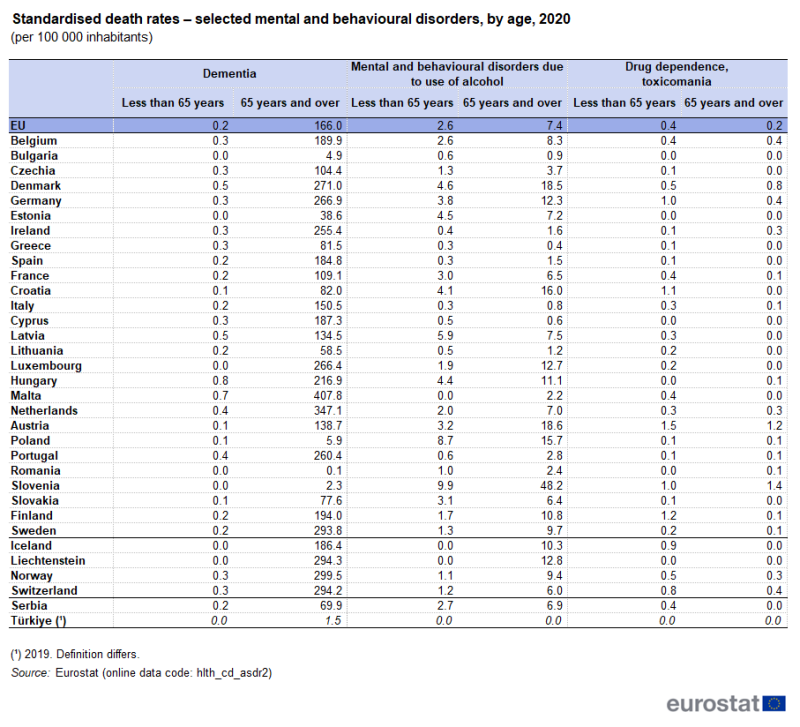

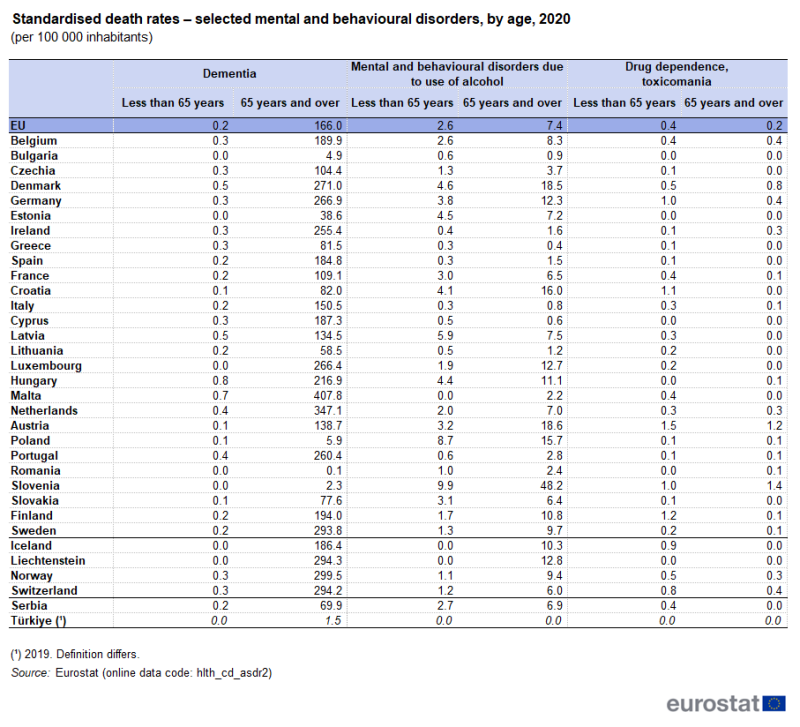

A more detailed analysis of causes of death for a selection of mental and behavioural disorders is presented in Table 1. The leading cause of death from mental and behavioural disorders was dementia, which accounts for 83 % of all deaths from mental and behavioural disorders in the EU in 2020. The standardised death rate for those over 65 years was 166 deaths from dementia per 100 000 people over 65 years in 2020; this is over 790 times higher than the standardised death rate for dementia in those under 65 years (0.2 per 100 000 people under 65 years).

The highest standardised death rate for dementia in those over 65 years was recorded in Malta (407.8 deaths from dementia per 100 000 people aged over 65 years), followed by the Netherlands (347.1 deaths from dementia per 100 000 people aged over 65 years). The lowest standardised death rates were reported in Romania, Slovenia and Bulgaria (all under five deaths from dementia per 100 000 people aged over 65 years).

The second leading cause of death from mental and behavioural disorders was due to the use of alcohol. This was also the leading cause of death from mental and behavioural disorders in those under 65 years, with 2.6 deaths per 100 000 people under 65 years; this accounts for 64 % of deaths from mental and behavioural disorders in this age group. Slovenia reported the highest standardised death rate for deaths from mental and behavioural disorders due to the use of alcohol in both age groups (9.9 in the younger age group and 48.2 in the older age group).

In 2020, the only mental and behavioural disorder in the EU for which the standardised death rate was higher among those under 65 years was for drug dependence, also known as toxicomania. Analysis by country shows that in both age groups the standardised death rate for toxicomania ranged between 0.0 and 1.5 deaths per 100 000 inhabitants. This standardised death rate was higher for those under 65 years in 17 of the 27 Member States.

Males were 3.8 times as likely as females to die from intentional self-harm

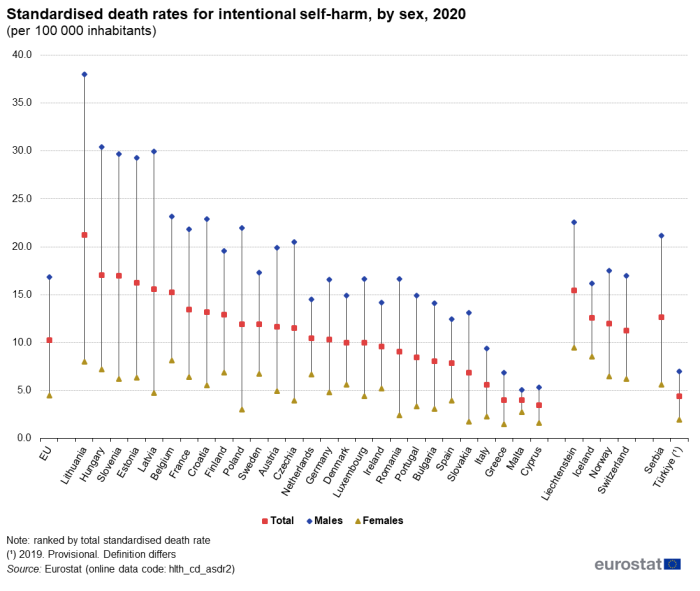

In 2020, the standardised death rate for intentional self-harm (ICD10 codes X60–84 and Y87.0) was 10.2 per 100 000 inhabitants for the EU, with the rate for males 3.8 times as high as that for females (see Figure 1). It should be noted that the comparability of data on intentional self-harm is thought to be limited due to an under reporting of suicides in some EU Member States (possibly due to cultural stigma and other reasons).

(per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_cd_asdr2)

Across the EU Member States, the highest standardised death rate for intentional self-harm in 2020 was recorded for Lithuania (21.3 per 100 000 inhabitants), followed at some distance by Hungary, Slovenia, Estonia, Latvia and Belgium, each with rates within the range of 15.0–17.1 per 100 000 inhabitants. Rates between 5.0 and 13.5 per 100 000 inhabitants were recorded for most of the other EU Member States, Greece, Malta (both 4.0 per 100 000 inhabitants) and Cyprus (3.5 per 100 000 inhabitants) below this range.

In all EU Member States, standardised death rates for intentional self-harm for males were higher than those for females in 2020, ranging from 1.9 times as high in Malta to 7.3 times as high in Poland. The largest absolute difference was recorded in Lithuania, where the rate for females was 8.0 per 100 000 inhabitants and the rate for males was 38.0 per 100 000 inhabitants.

Mental healthcare

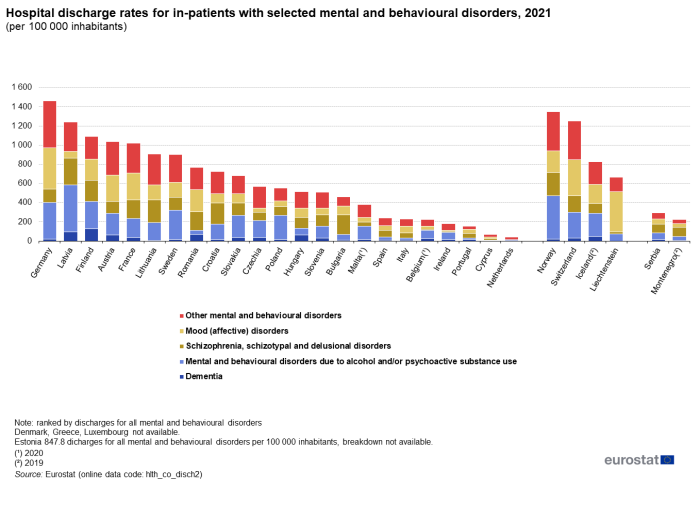

In 2021 there were 3.1 million in-patients with mental and behavioural disorders who were discharged from hospitals in the EU Member States for which data are available (2020 data for Germany and Malta; no recent data for Denmark, Greece and Luxembourg). In Germany, there were 1.2 million in-patient discharges among people treated for mental and behavioural disorders in 2021. There were only two other EU Member States that recorded in excess of 200 000 in-patient discharges in 2021 – France and Poland – while these diseases accounted for less than 10 000 in-patient discharges in Ireland, the Netherlands, Malta and Cyprus.

Relative to population size, Germany recorded the highest number of in-patient discharges for mental and behavioural disorders in 2021, with 1 463 discharges per 100 000 inhabitants. Latvia, Finland, Austria and France also recorded more than 1 000 in-patient discharges for mental and behavioural disorders per 100 000 inhabitants. This was 15 times as high as the equivalent ratios for Cyprus and the Netherlands, where the lowest rates were recorded (68 and 40 in-patient discharges per 100 000 inhabitants, respectively). In the other Member States for which data are available this rate was between 153 and 908 in-patient discharges per 100 000 inhabitants.

Figure 2 shows the breakdown of discharges by diagnosis, for selected mental and behavioural disorders. Dementia accounted for the smallest proportion of hospital discharges in 19 of the 23 EU Member States for which data are available, ranging from 1.4 discharges per 100 000 inhabitants in the Netherlands, to 126.6 discharges from dementia per 100 000 inhabitants in Finland.

(per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_co_disch2)

In 2021, mental and behavioural disorders due to alcohol and/or psychoactive substance use accounted for 33 % of hospital discharges from mental and behavioural disorders in the EU (no data for Denmark, Greece and Luxembourg). The highest number of discharges relative to the population from mental and behavioural disorders due to alcohol and/or psychoactive substance use was reported in Estonia with 485.7 hospital discharges per 100 000 inhabitants. The lowest number of discharges was reported in the Netherlands and Cyprus, with 9.9 and 3.6 discharges per 100 000 inhabitants, respectively). In the other Member States for which data are available this figure ranged from 18 to 382 discharges per 100 000 inhabitants.

Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders, and mood (affective) disorders accounted for 27 % and 24 % of hospital discharges from mental and behavioral discharges among the EU Member States for which data are available. These figures varied greatly between Member States.

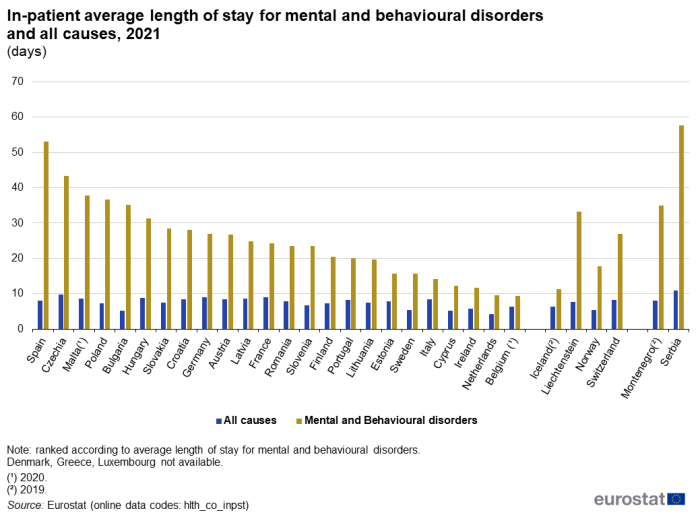

Particularly long average length of stay for in-patients with mental and behavioural disorders

Figure 3 presents an analysis of the average length of hospital stays for in-patients treated for mental and behavioural disorders and for all causes in 2021. The average length of stay for in-patients treated for mental and behavioural disorders ranged from 9.4 days in Belgium (2020 data) and 9.5 days in the Netherlands, and up to 53.1 days in Spain and 43.4 days in Czechia.

In nearly all of the EU Member States, these were the longest average lengths of stay of all the categories in the International Shortlist for Hospital Morbidity Tabulation (ISHMT). Only Belgium, Italy and Cyprus recorded a higher average length of stay for a different category. The average length of stay for in-patients treated for mental and behavioural disorders was 1.5 and 1.7 times higher than the average for all causes in Belgium and the Netherlands; and was 6.6 and 6.8 times higher in Spain and Bulgaria.

(days)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_co_inpst)

Healthcare beds and personnel

Increasing numbers of psychiatrists in most Member States

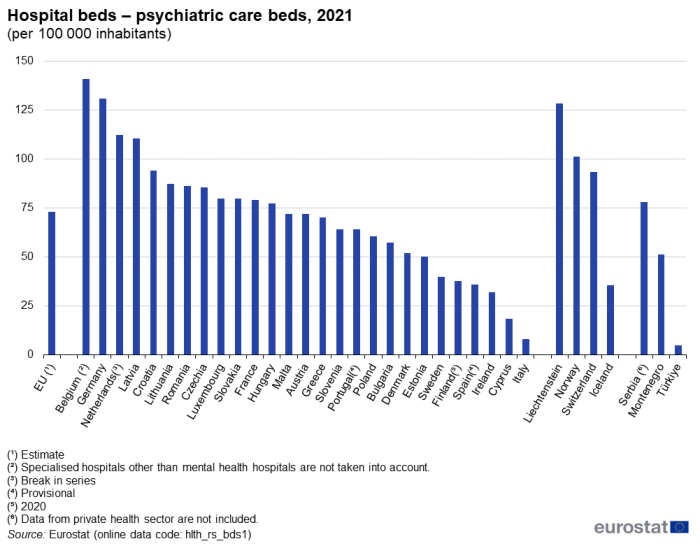

In 2021, there were 327 000 psychiatric care beds in hospitals in the EU, equivalent to 14 % of all hospital beds.

Figure 4 presents data for the number of psychiatric care beds in hospitals relative to the size of population in 2021. Belgium reported the highest number of psychiatric care beds in hospitals, with 141 psychiatric care beds per 100 000 inhabitants. Germany, the Netherlands (break in series) and Latvia also recorded more than 100 psychiatric care beds per 100 000 inhabitants. Italy was the only country to report less than 10 psychiatric care beds per 100 000 inhabitants (8.0). In the other Member States the number of psychiatric care beds was between 18.4 and 94.0 per 100 000 inhabitants.

(per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_rs_bds1)

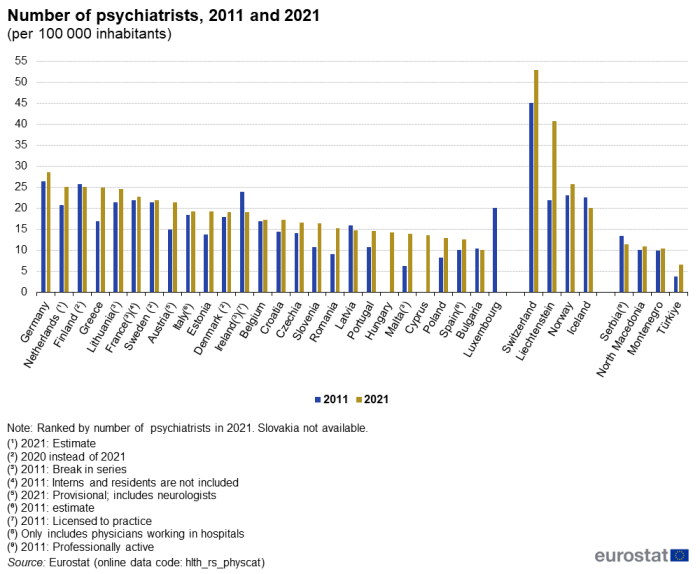

Relative to the population, the number of psychiatrists rose in the vast majority of EU Member States between 2011 and 2021. There was an increase recorded in 19 out of the 23 Member States for which data are available (only partial data for Luxembourg and no recent data for Slovakia). The biggest increases were in Greece, Malta, Austria and Romania, where the number of psychiatrists increased by more than 6.0 per 100 000 inhabitants between 2011 and 2021.

By contrast, Ireland reported the greatest fall in the number of psychiatrists relative to population size: down 4.9 psychiatrists per 100 000 inhabitants (note the break in series). Latvia, Finland and Bulgaria were the only other Member States to report a fall in their number of psychiatrists relative to population size; in each case the reduction was smaller than 1.2 per 100 000 inhabitants.

(per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_rs_physcat)

Extent of depressive disorders and healthcare personnel (Survey data)

Females reported depressive disorders more often than males

Depressive disorders cover single depressive episodes and recurrent depressive disorders (ICD10 codes F32–33). In typical depressive episodes, the patient suffers from a lowering of mood, reduction of energy, and a decrease in activity. The patient’s capacity for enjoyment, interest, and concentration is reduced, and marked tiredness after even minimum effort is common. Sleep is usually disturbed and appetite diminished; self-esteem and self-confidence are almost always reduced and, even in a mild form, some ideas of guilt or worthlessness are often present.

The third wave of the European health interview survey (EHIS) was conducted for 2019 and covers persons aged 15 years and over. The survey included questions on self-assessment of an individual’s health and data on chronic diseases diagnosed by a medical doctor and which occurred during the previous 12 months. These data are available for all EU Member States, Iceland, Norway, Serbia and Türkiye.

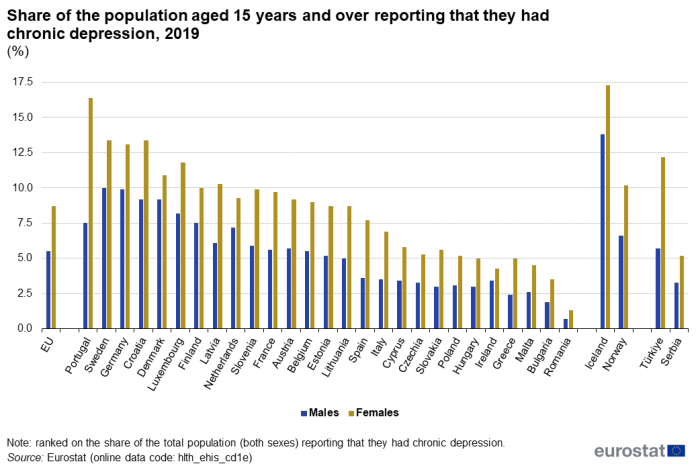

In 2019, 7.2 % of the EU population aged 15 years and over reported having chronic depression. At 12.2 %, Portugal had the highest share of its population reporting chronic depression among the EU Member States, while double-digit shares were also recorded in Sweden, Germany, Croatia, Denmark and Luxembourg; an even higher share was recorded in Iceland (15.6 %). The proportion of people reporting depression was no more than 4.0 % in Hungary, Ireland, Greece, Malta, Bulgaria and Romania.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_cd1e)

The proportion of people aged 15 years and over who had depressive disorders was higher for females than for males in each of the EU Member States; this pattern was also repeated in Iceland, Norway, Serbia and Türkiye. In 2019, the share of females reporting chronic depression was highest in Portugal at 16.4 %, which contributed towards Portugal recording the largest gender gap: the share of females reporting chronic depression was 8.9 percentage points (pp) higher than the corresponding share for males. Gender gaps of at least 4.0 pp (with higher rates for females) were also recorded in Croatia, Latvia, Spain, France, Slovenia and Türkiye.

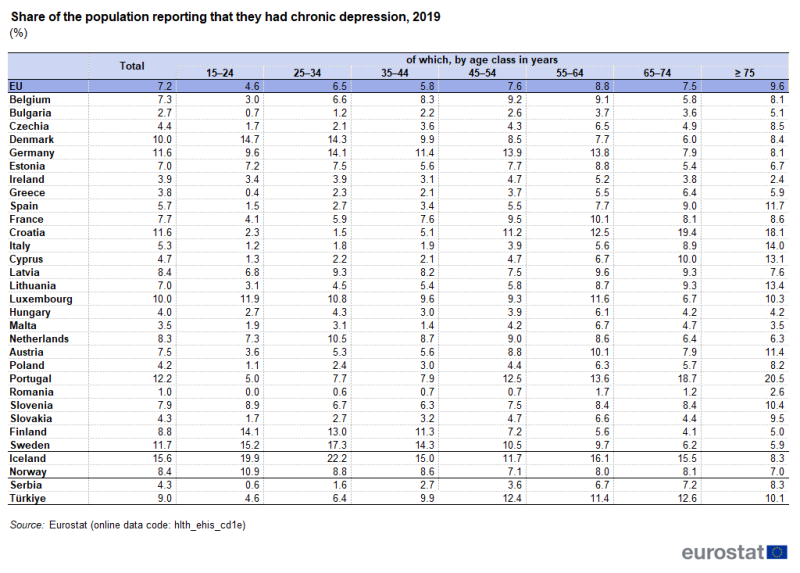

Almost 1 in 10 people in the EU aged 75 years and over reported chronic depression

Looking across the age groups in Table 2 from youngest to oldest, within the EU, the share of people reporting depression generally increased with age. The only exceptions to this pattern were for the classes covering people aged 25–34 years (where the prevalence of depression was higher than for people aged 35–44 years) and people aged 65–74 years (where the prevalence of depression was lower than for people aged 45–54 and 55–64 years).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_cd1e)

In 12 of the EU Member States, self-perceived chronic depression in 2019 peaked within the age group covering people aged 75 years and over. In Portugal, more than one in every five people aged 75 years and over reported having chronic depression. In another six of the Member States the share of people reporting chronic depression was highest among people aged 55–64 years and in two others it was highest between 65-74 years of age. By contrast, the highest share of people reporting chronic depression in Belgium was among those aged 45–54 years (9.2 %), while in Sweden, Germany and the Netherlands it was among those aged 25–34 years and in Denmark, Finland and Luxembourg it was among those aged 15–24 years. The pattern in Denmark and Finland was almost the reverse of the general situation witnessed for the whole of the EU insofar as the highest proportion of the population reporting chronic depression was recorded among those aged 15–24 years, a share that fell with age through to those aged 65–74 years, before increasing among those aged 75 years and over.

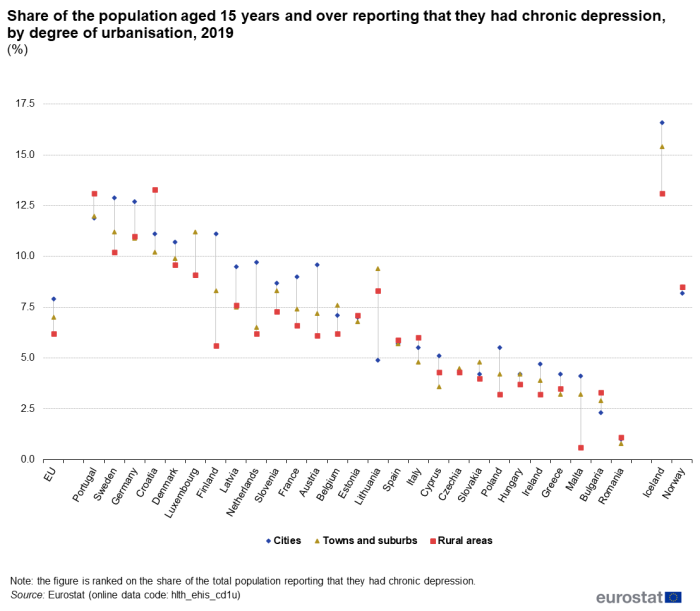

People living in EU cities were most likely to report chronic depression disorders

Except for the demographic factors analysed so far, the prevalence of chronic depression is also related to the degree of urbanisation. Figure 7 reveals that people aged 15 years and over, living in cities were most likely to suffer from chronic depression. In 2019, 7.9 % of people living in cities in the EU reported depression, higher than the shares for people living in towns and suburbs (7.0 %) or in rural areas (6.2 %).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_cd1u)

Concerning the analysis by degree of urbanisation, the majority of EU Member States can be classified into two distinct groups displaying opposite patterns: those in which the chronic depression rate was higher for people living in cities and those in which rural areas accounted for the highest rates of chronic depression. In the first group, the highest proportions were recorded in Sweden (12.9 %), Germany (12.7 %), Finland (11.1 %) and Denmark (10.7 %). Among the seven Member States composing the second group, Croatia (13.3 %) and Portugal (13.1 %) recorded the highest rates of chronic depression among people living in rural areas. In Luxembourg, Lithuania, Belgium, Slovakia and Czechia, the highest rates for chronic depression were recorded for people living in towns and suburbs; they ranged from 4.5 % in Czechia to 11.2 % in Luxembourg.

Healthcare activities

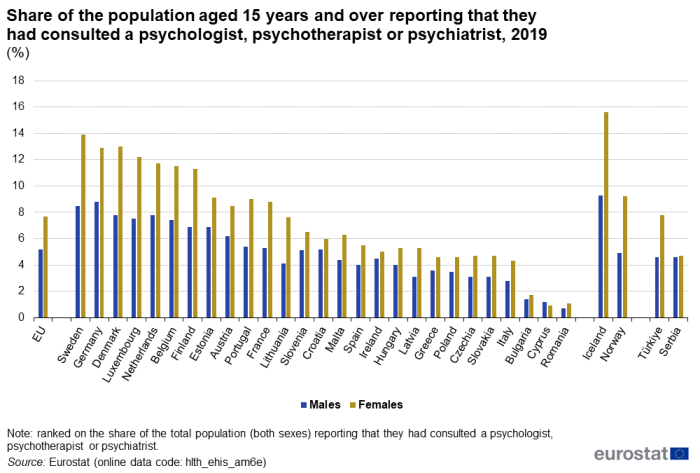

Psychologists study the mind and its functions, in particular in relation to individual and social behaviour. The third wave of the EHIS included questions asking respondents about their medical consultations with various specialists, including psychologists, psychotherapists or psychiatrists.

On average, the percentage of persons aged 15 years and over who reported having consulted a psychologist, psychotherapist, or psychiatrist in the 12 months prior to the 2019 EHIS survey was higher among females (7.7 %) than males (5.2 %). This pattern was apparent across almost all EU Member States (see Figure 6), the only exception being Cyprus (where the proportion was higher for males than for females). The largest gender differences were in Sweden (5.4 pp), Denmark (5.2 pp) and Luxembourg (4.7 pp); there was an even larger gender gap observed in Iceland (where the difference between the sexes was 6.3 pp).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_am6e)

Overall (males and females combined), the proportion of the population aged 15 years and over that had consulted a psychologist, psychotherapist or psychiatrist in the 12 months prior to the 2019 EHIS survey was between 3.5 % and 9.9 % in most EU Member States. The shares in Denmark (10.4 %), Germany (10.9 %) and Sweden (11.2 %) were above this range; the shares in Bulgaria (1.5 %), Cyprus (1.0 %) and Romania (0.9 %) were below it. Iceland also recorded a high proportion (12.6 %).

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

Key concepts

An in-patient is a patient who is formally admitted (or ‘hospitalised’) to an institution for treatment and/or care and stays for a minimum of one night or more than 24 hours in the hospital or other institution providing in-patient care. An in-patient or day care patient is discharged from hospital when formally released after a procedure or course of treatment (episode of care). A discharge may occur because of the finalisation of treatment, signing out against medical advice, transfer to another healthcare institution, or because of death.

The number of deaths from a particular cause of death can be expressed relative to the size of the population. A standardised (rather than crude) death rate can be compiled which is independent of the age and sex structure of a population. This is done as most causes of death vary significantly by age and according to sex and the standardisation facilitates comparisons of rates over time and between countries.

Mental and behavioural disorders are often highly stigmatised and diagnostic criteria for different mental and behavioural disorders often have many overlapping symptoms making diagnoses difficult and variable. Consequently, mental and behavioural disorders are known to be greatly underdiagnosed, and coding practices may vary significantly between countries[1].

Healthcare resources and activities

Statistics on healthcare resources (such as beds and personnel) and healthcare activities (such as information on hospital discharges) are documented in this background article which provides information on the scope of the data, its legal basis, the methodology employed, as well as related concepts and definitions.

For hospital discharges and the length of stay in hospitals, the International Shortlist for Hospital Morbidity Tabulation (ISHMT) is used to classify data from 2000 onwards; Chapter V covers mental and behavioural disorders.

- Dementia (0501)

- Mental and behavioural disorders due to alcohol (0502)

- Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of other psychoactive substances (0503)

- Mood [affective] disorders (0504)

- Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (0505)

- Other mental and behavioural disorders (0506)

For country specific notes, please refer to the annexes at the end of the national metadata reports accessible from links at the beginning of the European metadata report.

The Healthcare non-expenditure statistics manual provides an overview of the classifications, both for mandatory variables and variables provided on voluntary basis

Health status

Self-reported statistics covering the health status of the population for a range of chronic diseases is provided by the European health interview survey (EHIS). This source is documented in more detail in this background article which provides information on the scope of the data, its legal basis, the methodology employed, as well as related concepts and definitions. The data presented in this article refer to the share of the population aged 15 years and over reporting to have been diagnosed by a medical doctor with depression which occurred during the 12 months prior to the survey.

Causes of death

Statistics on causes of death provide information on mortality patterns, supplying information on developments over time in the underlying causes of death. This source is documented in more detail in this background article which provides information on the scope of the data, its legal basis, the methodology employed, as well as related concepts and definitions.

The Eurostat causes of death data collection is based on confirmed death certificates established by medical experts assessing the underlying cause of death. There is a difference in the coding of cases of deaths due to mental and behavioral disorders, where the mental and behavioral disorder was the established underlying cause of death versus where death occurred in someone who was suffering from a mental and behavioral disorder at the time of death.

Causes of death are classified according to the European shortlist (86 causes), which is based on the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10). Chapter V of the ICD-10 covers mental and behavioural disorders and Chapter XX covers external causes of mortality (including intentional self-harm).

- F00–F09 Organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders

- F10–F19 Mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use

- F20–F29 Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders

- F30–F39 Mood [affective] disorders

- F40–F48 Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders

- F50–F59 Behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors

- F60–F69 Disorders of adult personality and behaviour

- F70–F79 Mental retardation

- F80–F89 Disorders of psychological development

- F90–F98 Behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence

- F99 Unspecified mental disorder

- X60–X84 and Y87.0 Intentional self-harm

Symbols

Tables in this article use the following notation:

| Value in italics | estimate or provisional data; |

| Value is – | not relevant or not applicable; |

| Value is : | not available. |

Context

Mental and behavioural disorders make up one of the largest categories of diseases in the EU. In 2021, the number of in-patient bed days for mental and behavioural disorders in the EU was 83 million (2020 data for Malta and Belgium; no data for Denmark, Greece and Luxembourg), which was the largest number among all categories of diseases and conditions, ahead of diseases of the circulatory system. Nevertheless, it is believed that many mild to moderate mental disorders are under-diagnosed and consequently untreated and not reported within these official statistics.

As well as being important for individuals, good mental health is important for society. Mental health issues impact economic performance through productivity losses and increased work-disability costs and may also create a burden for educational and justice systems.

In November 2005, the European Commission published a Green Paper Improving the mental health of the population – Towards a strategy on mental health for the European Union. Subsequently, the European pact for mental health and well-being was launched, identifying five priority areas:

- prevention of depression and suicide;

- mental health in youth and education;

- mental health in workplace settings;

- mental health of older people;

- combating stigma and social exclusion.

In 2009 and 2011, the pact was implemented by way of five conferences, one for each priority; two further conferences were held on ‘Mental health: challenges and possibilities’ (October 2013) and ‘Youth mental health’ (December 2014).

In 2013, a joint action on mental health and well-being was launched. This action built on previous work developed under the European pact and was carried out until 2018. Its objective was to contribute to the promotion of mental health and well-being, the prevention of mental disorders, and the improvement of care and social inclusion of people with mental disorders in Europe.

The joint action resulted in the European Framework for Action on Mental Health and Wellbeing, which supports EU Member States to review their policies and share experiences in improving policy efficiency and effectiveness. It aims to:

- develop mental health promotion and prevention and early intervention programmes;

- ensure the transition to comprehensive mental health treatment and quality care;

- strengthen knowledge, evidence and best practice sharing in mental health.

Contributing to the European Year of Youth, and as part of the EU4Health 2022 work plan, two new projects aim to improve the mental health of children, young people and their families through the implementation of best practice. The practices concerned are:

- a sport-based support programme to improve life skills and social, psychological and emotional resources among socially vulnerable children and adolescents; and

- a two-step intervention to support mental health and well-being of young people and their families in vulnerable situations.

Mental health and neurological disorders is one of the five main strands covered by the European Commission’s Healthier together – EU non-communicable diseases (NCD) initiative. The initiative was launched in December 2021 and aims to support EU countries in identifying and implementing effective policies and actions to reduce the burden of major NCDs and improve citizens’ health and well-being.

The Commission has also mobilised €9 million from the EU4Health programme to help people fleeing Ukraine in urgent need of mental health and trauma support.

In 2023, the Commission added a pillar to the European Health Union on a new comprehensive approach to mental health. This approach is a first and important step to put mental health on par with physical health and to ensure a new, cross sectoral approach to mental health issues. With 20 flagship initiatives and €1.23 billion in EU funding from different financial instruments, the Commission will support Member States putting people and their mental health first.

Under this initiative the EU will take a holistic approach to mental health, based on three guiding principles:

- adequate and effective prevention,

- access to high quality and affordable mental healthcare and treatment,

- reintegration into society after recovery.

link